You can tuna fish, but you can't tune a piano. Wait, what?

Okay, that's not quite true. You can tune a piano, but only approximately. It turns out that the mathematics behind the 12-tone scale used in most Western music hides some sinister secrets.

Let's start with the basics. Behind every key on a piano are 1–3 strings, which have been tensioned so that when the strings are struck they will ring out at a specific frequency. Each note is associated with a distinct frequency, and keys are arranged such that the pitch of the notes increases from left to right.

So what determines the frequency of each key? In a nutshell, we start from a reference note which we assign a specific frequency to, and figure out the frequency of the rest of the notes based on their harmonic relationships. The initial note is known as the pitch standard. In modern times, the most common pitch standard is A4 = 440 Hz, or just A440.

This is what A4 sounds like on my piano:

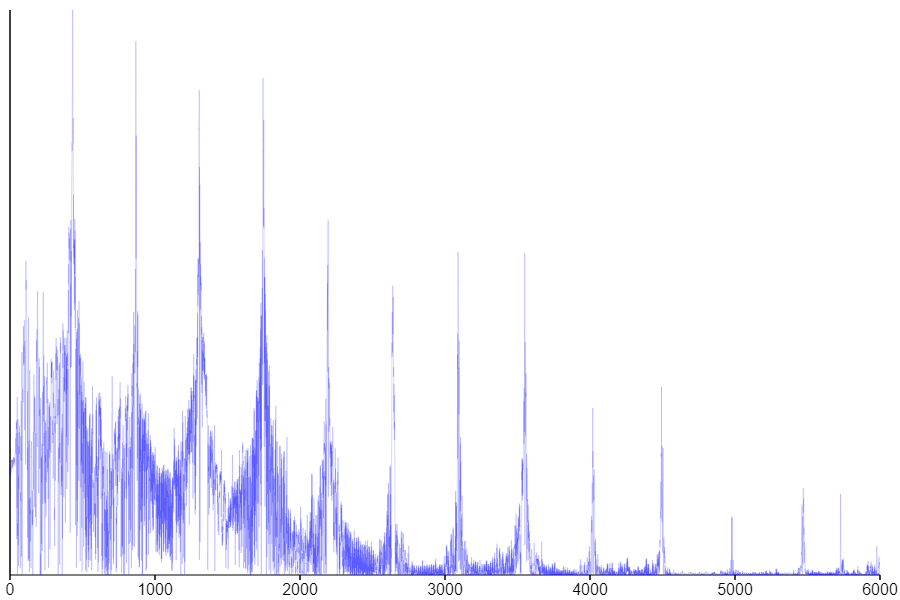

Ironically, my piano is pretty badly out of tune, but that doesn't matter for this demonstration. I can use a bit of math to take the sound and dissect it into the individual frequencies that make it up, kind of like how a prism can split light into its color components. Here is the resulting spectrum:

There's a big peak representing the fundamental frequency, but there are also a bunch of extra peaks, which are known as overtones or partials. Notice that the peaks are evenly spaced! This is a result of the physics of standing waves: whenever a wave is confined to a finite space, the resulting pattern of oscillation will be the sum of a series of normal modes, whose frequencies are integer multiples of the fundamental frequency. In this case, we see overtones at 880 Hz, 1320 Hz, 1760 Hz, and so on. The fundamental frequency and its overtones form the harmonic series.

The same phenomenon is actually exhibited by many other oscillating systems besides strings. For example, air in a tube is also confined to resonating at multiples of the tube's fundamental frequency. This is why, for a given fingering, a French horn player is restricted to playing notes within the harmonic series. In fact, even the quartz oscillators that are so ubiquitous in modern electronics can be made to vibrate at a multiple of its fundamental frequency.

The harmonic series is crucial to the Western tradition of music, where notes that share a lot of overtones are generally perceived as more consonant (as opposed to dissonant). As a result, the relationships between successive members of the harmonic series essentially serve as the building blocks of harmony, and they've been assigned names to reflect their importance.

Try it for yourself—click the Play button to hear the intervals formed by the harmonic series!

Okay, so we're making some real progress. We know from the circle of fifths that we can start from any note and advance in perfect fifths to cycle through the other 12 notes before returning to the starting note. This is the idea behind Pythagorean tuning.

If you actually try this, you will realize that it doesn't quite work. We saw in the previous demo that a perfect fifth is represented by a frequency ratio of 3:2. So if we multiply the frequency of a note by 3/2 twelve times, we would expect to come back to the same note a few octaves up. Yet (3/2)12 is approximately 129.746, which is not a power of two!

The reason for this is mathematical. The square root of two is irrational, meaning that it is impossible to create it by multiplying together rational numbers like 3/2. In fact, pretty much all the intervals are slightly wrong. The problem becomes very apparent when you try to play chords using our DIY tuning system:

The rapid warbling sound you hear is an acoustic phenomenon known as beating, which occurs when two tones that are slightly out of tune are played together. (This may be hard to hear without headphones). For reference, here's what the same chord sounds like if we calculate the frequency of the other two notes based on the root note times the frequency ratios we figured out earlier:

Essentially, the problem is that a note's exact frequency may vary depending on what interval it's in. This is less a problem if you play an instrument where you have full control over what pitch is being played, but on a piano, the frequencies of each note are fixed. Thus, it is impossible to tune a piano such that every interval remains pure.

Well. What do we do, then?

The "Solution" §

Over the centuries, a littany of different tuning systems have been devised to deal with this problem. Each system dealt with the unavoidable compromises of harmony in different ways to suit the needs of composers of their time, and in turn, their limitations influenced how music was written. However, in the modern era, one particular scheme has come to dominate music: equal temperament. What's a temperament? I think Wikipedia provides an excellent, succinct definition:

A temperament is a tuning system that slightly compromises the pure intervals of just intonation to meet other requirements.

Equal temperament does not use integer ratios. Instead, a semitone is defined to have a frequency ratio of the twelfth root of 2. This way, twelve semitones will produce a perfect octave every time. Here's what the chord from earlier sounds like under equal temperament:

If you give it a listen, you might say: I can still hear beating—what's the big idea? You're right; under equal temperament, every interval besides the octave is a little bit impure. But this is where equal temperament shines: it sounds acceptable when playing in any key, while most tuning systems based on just intonation become severely dissonant in keys other than the one they're based on. This is a dealbreaker for modern music, which often makes use of modulation. Having to retune your piano every time you want to play in a different key is rather inconvenient!

Coda §

The history of tuning systems and how their evolution shaped Western music is absolutely fascinating, and this article only scratches the surface. Here are some videos and articles (some of which I used as references while writing this post), in case you'd like to learn more.

Ethan Hein's Tuning Is Hard dives deep into the details of tuning with just intonation.

This video uses a digital keyboard to demonstrate the fundamental flaw of just intonation.

Remember how I claimed that tuning systems aren't as important for instruments that can change pitches on the fly? That's mostly true, but it's still impossible to play everything in perfect harmony. An Italian mathematician named Giambattista Benedetti demonstrated this phenomenon through a series of "puzzles"—repeating melodies whose pitch would become sharper and sharper if one attempted to play them using only pure intervals. Adam Neely made an excellent video on the subject:

Bach may have composed The Well-Tempered Clavier to demonstrate how well temperament (a class of tuning systems that would eventually give rise to equal temperament) enabled music written in any key to sound good. Here is a performance of the first prelude in three different temperaments, accompanied by some very enlightening explanation of each tuning system.

Finally, MinutePhysics made a video seven years ago which first introduced me to the mathematical problems faced by tuning and inspired this article.

Also, music numbers.